China's Short Drama Industry Under Fire After Baby Actor Forced to Stay in Rain for 800 Yuan Fee

A viral post on China’s Weibo platform has ignited a fierce debate over the treatment of child actors in the country’s booming short drama industry, after a performer claimed a baby was forced to stay in the rain for a scene—earning just 800 yuan ($112) for the role. The controversy, which has drawn millions of comments and prompted a government response, highlights the systemic exploitation of young talent in a sector driven by speed and cost-cutting.

18 January 2026

The Controversy: A Baby in the Rain

A viral post on China’s Weibo platform has ignited a fierce debate over the treatment of child actors in the country’s booming short drama industry, after a performer claimed a baby was forced to stay in the rain for a scene—earning just 800 yuan ($112) for the role. The controversy, which has drawn millions of comments and prompted a government response, highlights the systemic exploitation of young talent in a sector driven by speed and cost-cutting.

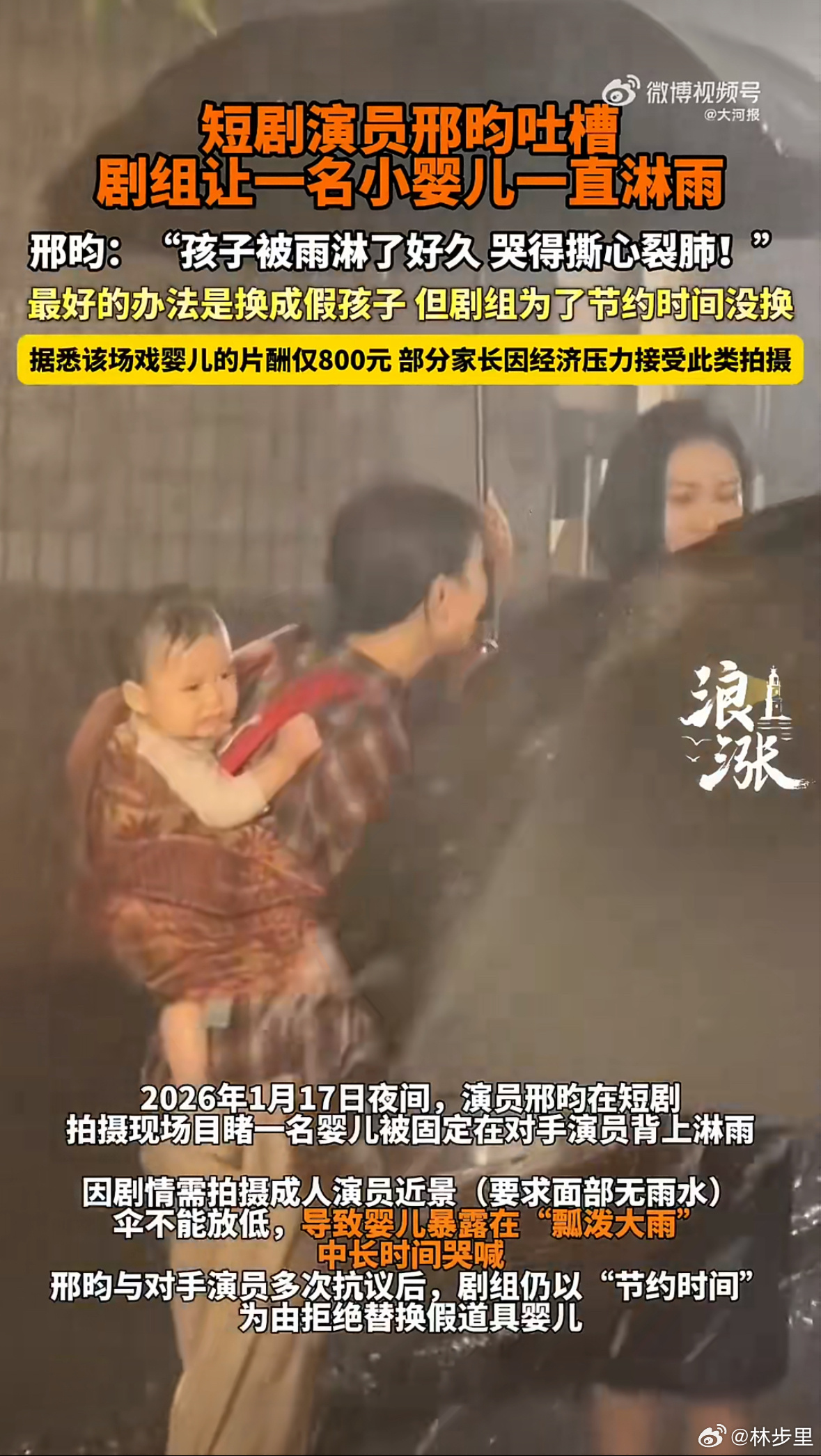

On January 17, 2026, short drama actor Xing Diao (邢昀) took to Weibo to expose the incident, sharing a video of a baby crying while being held in a simulated downpour. She alleged that the production team refused to use a prop baby for close-up shots, prioritizing efficiency over the child’s well-being. “The baby was in the rain for a long time, crying heartbreakingly,” Xing wrote. “The best solution was to switch to a prop baby, but the crew said it would take too much time.”

The post quickly went viral, with the hashtag #短剧淋雨婴儿片酬仅800元# (#ShortDramaBabyInRainPaidOnly800Yuan#) trending on Weibo. The controversy was amplified by the paltry fee: 800 yuan, a sum that barely covers medical costs for a potential cold or pneumonia—risks heightened by exposure to cold, wet conditions. “Is 800 yuan enough to treat a cold, fever, or pneumonia?” one user asked. “The crew has so many people, and even adult actors can’t stand the rain—what about a baby?”

The image of the crying baby, captured in the rain with crew members nearby, became a symbol of the industry’s neglect. (See Image 1: A baby actor is held in a simulated downpour during a short drama shoot, with text highlighting the actor’s complaint about the crew’s refusal to use a prop baby.)

Public Outrage: Weibo Erupts in Anger

Public outrage on Weibo was immediate and visceral. Users flooded the platform with comments condemning the crew’s actions and questioning the parents’ decisions. “This child is too pitiful,” one user wrote. “How can parents agree to this for money?”

Xing Diao, the actor who exposed the incident, joined the conversation, noting that the problem was widespread. “Many child actors in short dramas are treated this way,” she said. “I really hope there are fewer child roles, so they can go back to school and have a normal childhood.”

The hashtag #短剧演员吐槽剧组让孩子一直淋雨# (#ShortDramaActorComplainsCrewMadeChildStayInRain#) trended alongside the original, with users sharing personal stories of witnessing similar exploitation. “I’ve seen kids in short dramas working 16-hour days, exhausted and falling asleep on set,” one commenter said. “This isn’t just about the rain—it’s about a system that treats children like props.”

The image of Weibo comments, including Xing’s response, underscores the public’s anger and the actor’s call for change. (See Image 4: A screenshot of Weibo comments on the viral post, with Xing Diao responding to users.)

Government Steps In: New Rules to Protect Child Actors

The controversy prompted a swift response from China’s State Administration of Radio and Television (SART), which on January 8, 2025, issued new guidelines to protect child actors in micro-short dramas. The rules, titled “Management Tips for Children’s Micro-Short Dramas,” explicitly ban overwork and unsafe scenes, requiring written consent from parents and ensuring children’s physical and mental health.

“Children’s actors must not be subjected to overwork, and they cannot perform violent, terrifying, or emotionally distressing scenes beyond their capacity,” the guidelines state. The administration also emphasized the need for proper rest, education, and safety measures, such as providing warm water and shelter during rain scenes.

The new rules come amid growing scrutiny of the short drama industry’s “7 days, 100 episodes” model, which pressures crews to produce content at breakneck speed. For child actors, this often means 16-hour workdays, with little time for rest or play. “The industry’s focus on speed has turned children into commodities,” said Li Wei, a child welfare advocate. “These guidelines are a step forward, but enforcement will be key.”

The image highlighting the 800 yuan fee and the question of medical costs reinforces the urgency of the issue. (See Image 6: A graphic from Weibo emphasizing the 800 yuan fee and the risk of pneumonia.)

The '7 Days, 100 Episodes' Model: A Systemic Problem

The “7 days, 100 episodes” model, which has defined the short drama boom in China, is at the heart of the problem. Producers, eager to capitalize on viral trends, compress production timelines to maximize profits, often at the expense of quality and safety. For child actors, this means being forced into dangerous or uncomfortable situations—like the rain scene—to meet deadlines.

“Crews cut corners to save time and money,” said Zhang Ming, a former short drama director. “Using a prop baby takes extra effort, so they choose the easy way out—even if it harms the child.”

The image of the baby in the rain, repeated in the viral post, serves as a stark reminder of the human cost of the industry’s growth. (See Image 5: The baby actor is held in the rain, with crew members nearby, emphasizing the ongoing exploitation.)

As the debate continues, many are calling for stricter enforcement of the new guidelines and greater accountability for producers. “Children are not props,” Xing Diao said. “They deserve to be treated with respect.”

The controversy has also sparked a broader conversation about the ethics of child labor in entertainment, with users demanding that the industry prioritize children’s well-being over profit. “This isn’t just about one baby—it’s about changing a system that values speed over humanity,” one Weibo user wrote.